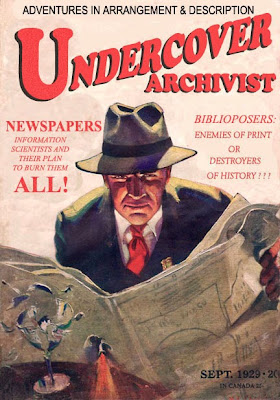

Libraries have been treating newspapers like bird cage liners for decades, taking yesterday’s edition from the little sticks on the hanging rack, throwing it onto a pile of its fellows in the corner for a week or two, and then putting today’s copy on the stick to start the process all over again. Eventually the stack in the corner had its purgatory status resolved by either being fed into the hell of the recycle bin or taken to the heaven of the microfilm room. Alas, the stop under the camera was only an illusory paradise, for after its filming the stack found its way to the rubbish anyway. Writer Nicholson Baker decried the practice as recently as two decades ago, but libraries and archival allies responded vehemently to Baker’s grousing, pointing out the ephemeral nature of newsprint demanded its migration to microfilm for long term preservation. Besides, argued the librarians, we don’t have the space to store all those stacks of crumbling dailies after their text is rendered onto a compact reel of silver halide film.

Fast forward to the new world order of the Information Scientist and the Biblioposer. To these nefarious characters even microfilm is a waste of space and their never-ending conspiracy to change “things” into “zeros and ones” has given them an argument for pitching even microforms into the insatiable “we-are-going-green” dustbins. Never mind the fact that microfilm can be read with no more fancy equipment than a candle and a magnifying glass, to the Information Scientist anything not on the screen is junk taking up space. In fact, with newspapers turning more and more to an online rather than physical presence, we can cut out the middleman entirely and simply “archive” the web pages of the New York Times.

Somehow that option leaves us cold here at True Archives. We are prepared to work undercover to save these artifacts and insist that the best place for microfilm and its “floppy disk” cousin, microfiche, is with us where it can be safely stored amidst other three-dimensional information bearing objects. While they are at it, let the “libraries” also give us their microform reading machines too; after all, those dinosaurs are just getting in the way of the computers.

A display forum to broadcast and share the hundreds of altered pulp magazine and comic book images I have created to illustrate the tensions between traditional archival management and the demands of the digital age.

Friday, May 30, 2014

Monday, May 19, 2014

Banned of Brothers

If you have any familiarity with American libraries you are likely aware of an annual ritual called “Banned Book Week.” This non-event sets up a straw man of censorship that allows Biblioposers the opportunity to throw self-righteous mud pies at a fictitious target. There are so many aspects that make “Banned Book Week” a farce, but lets try to restrict ourselves to a few obvious ones.

1. True cases of codex censorship actually occurring in 21st century American public or academic libraries are virtually non-existent. That leaves only public school libraries, and if we are going to talk censorship and restrictions on freedom in that venue we can also discuss dress codes, behavior requirements, yearbook composition, and a host of other activities where students of minor age cannot do as they please.

2. The idea that impressionable youth can be protected from unsavory influences by simply removing a book from a repository is so laughably quaint in the internet age that even some ardent Christian fundamentalists can recognize the futility of the effort. That's why they home school or set up religious academies where they are free to censor all they want. Certainly the Information Scientist can understand the waste of time it takes to ban a book since his job is to steer youth to the screen rather than the printed page anyway.

3. The biggest threat to the future of the book and reading is the library itself, whose management routinely tosses out volumes based on user metrics that easily demonstrate declining circulation of just about everything except DVDs.

Really, what use is it for the Information Scientist to cry crocodile tears over the decision of a local school board to remove Catcher in the Rye from the high school library? The real issue here is kids who do not read anything at all, which is a form of censorship that is self-imposed and impossible to stop. It is time to move the books to the archives, where they will be saved from the ravages of current societal indifference.

1. True cases of codex censorship actually occurring in 21st century American public or academic libraries are virtually non-existent. That leaves only public school libraries, and if we are going to talk censorship and restrictions on freedom in that venue we can also discuss dress codes, behavior requirements, yearbook composition, and a host of other activities where students of minor age cannot do as they please.

2. The idea that impressionable youth can be protected from unsavory influences by simply removing a book from a repository is so laughably quaint in the internet age that even some ardent Christian fundamentalists can recognize the futility of the effort. That's why they home school or set up religious academies where they are free to censor all they want. Certainly the Information Scientist can understand the waste of time it takes to ban a book since his job is to steer youth to the screen rather than the printed page anyway.

3. The biggest threat to the future of the book and reading is the library itself, whose management routinely tosses out volumes based on user metrics that easily demonstrate declining circulation of just about everything except DVDs.

Really, what use is it for the Information Scientist to cry crocodile tears over the decision of a local school board to remove Catcher in the Rye from the high school library? The real issue here is kids who do not read anything at all, which is a form of censorship that is self-imposed and impossible to stop. It is time to move the books to the archives, where they will be saved from the ravages of current societal indifference.

Tuesday, May 13, 2014

Dude, Where's my Brain?

A colleague of mine had me read over his research paper before sending it off for publication and within that essay he observed that it is now possible for a person to hold almost the sum of human knowledge in the palm of the hand. These little computer-telephone-camera-whatever devices have indeed allowed modern man to empty his head of any memorization from individual telephone numbers to the location of the nearest beer store. What a boon for mankind! No more to be shackled to such mundane tasks of memorization, but freed to gaze upon the stars (and look down at a little screen to tell you the names of those stars).

Here at True Archives we know the illusion of knowledge is becoming more common than the genuine article, and we wonder what would become of our current generation of internet junkies should the earth endure a repeat session of the great Solar Storm of 1859. Back in those days the giant electromagnetic disruption only knocked out the telegraph systems, but imagine what would happen today? Aside from airplanes falling from the sky and hospitals unable to perform medical care, there would be millions of people unable to upload cute cat videos or post updates on what they had for lunch! Information Scientists would be mortified if such a catastrophe resulted in people actually referring to printed dictionaries, gazetteers, and encyclopedias to get their answers.

Here at True Archives we know the illusion of knowledge is becoming more common than the genuine article, and we wonder what would become of our current generation of internet junkies should the earth endure a repeat session of the great Solar Storm of 1859. Back in those days the giant electromagnetic disruption only knocked out the telegraph systems, but imagine what would happen today? Aside from airplanes falling from the sky and hospitals unable to perform medical care, there would be millions of people unable to upload cute cat videos or post updates on what they had for lunch! Information Scientists would be mortified if such a catastrophe resulted in people actually referring to printed dictionaries, gazetteers, and encyclopedias to get their answers.

Monday, May 5, 2014

Give Me Your Tired, Your Poor, Your Huddled Books Yearning to Survive

Once upon a time there was a special place that gave meaning to surrogates we used in everyday life. We used to exchange these substitutes without a thought about their representational value because we knew they symbolically held the same value as items stored inside that special place. Then, one day, some genius decided the items in the special place were no longer needed, and the surrogates we exchanged were to be valued on faith alone. Obviously that did not work, and the exchange items have been floating in limbo ever since. I’m speaking, of course, about United States currency, which used to base its value on the gold stored at Fort Knox, Kentucky. There is a reason why Goldfinger wanted to get into that bastion, and why James Bond had to stop him: without gold the dollar has no meaning. So it is with the books in our libraries that the evil Information Scientist wants scanned and destroyed: without the books, their images have no meaning.

I wish True Archives could claim credit for this beautiful analogy, but it belongs to Carl Posy, Head of the School of Religion and Philosophy of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and former Academic Director of the National Library of Israel. Carl spoke at our library in 2012 and described his gold standard theory, one which I hope every archivist will take to heart. Biblioposers work hand in hand with the Information Scientist, cheerfully feeding original books into the maw of destruction because they have always viewed the codex as a disposable commodity. Only the archivist, dedicated to the preservation of three-dimensional information bearing artifacts, is in a position to save the book, just like James Bond saved the gold at Fort Knox. He never stopped to question "why"...

I wish True Archives could claim credit for this beautiful analogy, but it belongs to Carl Posy, Head of the School of Religion and Philosophy of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and former Academic Director of the National Library of Israel. Carl spoke at our library in 2012 and described his gold standard theory, one which I hope every archivist will take to heart. Biblioposers work hand in hand with the Information Scientist, cheerfully feeding original books into the maw of destruction because they have always viewed the codex as a disposable commodity. Only the archivist, dedicated to the preservation of three-dimensional information bearing artifacts, is in a position to save the book, just like James Bond saved the gold at Fort Knox. He never stopped to question "why"...

Friday, May 2, 2014

The Cursive Divide

Archivists of a certain age (your humble correspondent included) grew up in a world where kids in kindergarten were routinely handed a thick pencil, a sheet of highly acidic ruled paper, and instructed how to block out the letters of the alphabet. Years later, under the patient guidance of different teachers, these ancient archivists also learned to pencil their alphabetic characters in cursive, and perform feats of calligraphic composition that would occasionally result in a somewhat legible paragraph or two written out in relative speed.

Fast forward to the world dominated by the evil Information Scientist and his minions, where school children are first taught the block letters and then pushed into learning the keyboard layout, skipping cursive writing altogether. So what, you may ask, what does it matter if our upcoming generations never learn to sign their names like John Hancock? The problem lies in our archives, my friends. Think of all the nineteenth and early twentieth century documents that reside in your collections. That handwriting they bear will be as unintelligible as the proverbial chicken scratchings to people who never learned how to write cursive themselves. All the scanning in the world forced by the Information Scientists won’t change this situation. It will simply result in millions of digital images that few, if any, will be able to decipher.

All is not dark, however, and even I can see one advantage in this brave new world where people sign their names with an "x". Here at True Archives we take all our uncensored notes in cursive while seated in faculty meetings or lectures, secure in the knowledge that our scribbling will remain a mystery to our younger colleagues.

Fast forward to the world dominated by the evil Information Scientist and his minions, where school children are first taught the block letters and then pushed into learning the keyboard layout, skipping cursive writing altogether. So what, you may ask, what does it matter if our upcoming generations never learn to sign their names like John Hancock? The problem lies in our archives, my friends. Think of all the nineteenth and early twentieth century documents that reside in your collections. That handwriting they bear will be as unintelligible as the proverbial chicken scratchings to people who never learned how to write cursive themselves. All the scanning in the world forced by the Information Scientists won’t change this situation. It will simply result in millions of digital images that few, if any, will be able to decipher.

All is not dark, however, and even I can see one advantage in this brave new world where people sign their names with an "x". Here at True Archives we take all our uncensored notes in cursive while seated in faculty meetings or lectures, secure in the knowledge that our scribbling will remain a mystery to our younger colleagues.

Thursday, May 1, 2014

A Book! A Book! My Kingdom for a Book!

How much time do we spend attempting to give millennials the illusion of research? We scan, we type in metadata, we build search engines, and we neglect our mountainous backlog of paper resources, all to provide a superficial sampling of documents for cursory review. What are the results of this Sisyphean task? An explosion of in-depth historical inquiry based on the time honored tasks of internal and external criticism of primary source materials? Here at True Archives we laugh at that conclusion. There seems to be little hope of a new Herodotus appearing suddenly as a result of our endless labor in rendering digital surrogates. Even if a scholar was able to take our pathetic sampling of images to compose a monumental tome, who would keep and maintain it? Certainly not the Information Scientist, who loves holding the historian hostage to a world of byte sized snippets of facts, custom made for skim reading and shallow understanding. In the future, the heroic Archivist must step forward to save the book in addition to the material that makes composition of the book possible.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)